Race, Faith and Truth

Diversity image, antoniomas/ Shutterstock.com

I was in my office on a quiet afternoon when I saw the car pull into the parking lot.

Those of us who work in churches are familiar with people stopping by seeking a bit of financial help. But people stop by churches for lots of reasons. It’s best to wait to see what they want before making assumptions.

As I watched the African-American gentlemen get out of his car, I sighed. My peaceful afternoon was going to be interrupted by yet another request for help. We could do that, but it would take some time. He came into the church and I greeted him.

“Hi, how are you?”

“Fine,” he said. “But I think I’m lost. I’ve got this appointment at a business near here, but I think I missed a turn. Can you help me figure out where it is?”

So why did I assume he was looking for a handout? The only variable was the color of his skin. And in that moment, I realized how quickly I make judgments about people based on stereotypes that lurk within me. And I was grateful that I had kept that stereotype to myself when I greeted the man.

It is not very difficult to understand why there is a black church and a white church in America today, or to realize that this structure will not change in the near future. The religious atmosphere created by the coming together of blacks (who were slaves) and whites (who were masters) tended to negate any possibility of developing the true unity and oneness that scripture proclaims for the church. The agendas of the slaves were vastly different from those of the masters. Unfortunately, conflict over agendas, both stated and unstated, continues to be one of the reasons that blacks and whites do not come together to worship.

Eventually, Butch invited me to come to his home and meet his family. I felt deeply honored and very eager to go. But every time I asked him to write directions to his place, he would change the subject. Finally one day with pen and paper in hand, I sat him down and said, "Look, Butch, how do you expect me to get to your house if you don't write out directions for me?"

Awkwardly he began to scribble on the paper. I was deeply sad when I realized the reason he had hesitated before was that he could barely write; I was ashamed at my insensitivity.

That small incident was very significant to me. I went home that night and both cried and cursed. I could not believe that someone as bright as Butch had hardly been taught to write. I was furious at a system that had given me so much and him almost nothing, simply by virtue of our skin color. By accident of birth, I had all the benefits and he all the suffering. I vowed again through angry tears to do everything I could to change that system.

Catherine Meeks

I suppose I could live my life saying, "I will never allow myself to try to understand white people. I will cut myself off from them. I will live my life as a black woman, and I'll just keep white people in boxes." But to do that means to keep myself cut off from a part of myself. And if white people do that about black people, I think the same is true: It keeps them cut off from a part of themselves.

For those of us who are Christians, I don't think we have any choice in the matter. I think God has made it clear that we're to be reconciled to God and each other. And if we're to be reconciled to each other, that includes everyone who happens to be in the world with us.

Reconciliation demands that you not take sides; it demands that you take a stand, I think—a stand that's maybe a merging of a lot of different pieces that represent several different kinds of philosophical stances. I think that one who chooses a road of reconciliation must be willing to look at more than one side of the coin.

WHO ARE WE? WHERE ARE WE GOING? And how are we going to get there? We can no longer answer these questions. Indeed, we have stopped asking them. But just as the future of blacks seemed to be in peril when integration was introduced decades ago, our future as a viable racial and ethnic group in this country will be greatly diminished unless a new model for racial and cultural development is established.

Jim Wallis

Jim Wallis sat down after the George Zimmerman verdict earlier this month to give his thoughts on race, faith, and truth.

"We live in our different worlds. That's not what we're supposed to do as the body of Christ."

IN SPIRITUAL AND BIBLICAL terms, racism is a perverse sin that cuts to the core of the gospel message. Put simply, racism negates the reason for which Christ died—the reconciling work of the cross. It denies the purpose of the church: to bring together, in Christ, those who have been divided from one another, particularly in the early church's case, Jew and Gentile—a division based on race.

There is only one remedy for such a sin and that is repentance, which, if genuine, will always bear fruit in concrete forms of conversion, changed behavior, and reparation. While the United States may have changed in regard to some of its racial attitudes and allowed some of its black citizens into the middle class, white America has yet to recognize the extent of its racism—that we are and have always been a racist society-—much less to repent of its racial sins.

A straight-shooting white friend once commented that whenever blacks and whites are together it's like there's a "big pile of poop in the middle of the room" that everybody sees and smells but pretends isn't there.

Suddenly, it seems, white people are seeing the racial divide as looming larger than before. Race, so often dismissed by white people as an insignificant factor in contemporary U.S. society, has acquired meaning—meaning that they were working hard to ignore.

Newt Gingrich addresses the Republican Leadership Conference. Christopher Halloran / Shutterstock

In light of the Zimmerman verdict, it’s taken my all to keep my spirit afloat. Upon the verdict’s announcement, I sat in shock and dismay, perplexed by the outcome. Despite anything revealed through the trail, a few facts remain: Martin, an unarmed teenager was followed and pursued by an armed adult, Zimmerman. Ultimately, Martin was fatally shot by Zimmerman, and Zimmerman’s received no legislative punishment for killing Martin.

Upon awakening from the trance of the verdict, I began crying as I held my four-month old son. I wept because as an African-American male, I’m fully cognizant of how dark brown skin will exacerbate his odds of being profiled and criminalized as Martin was. I am also aware that the neighborhood we reside in, by choice, on account of our faith, also increases his chances of being stereotyped. Nevertheless, irrespective of how stacked the odds are against someone, odds never define a person’s existence. Through God’s grace, communal support, social capital, hard work, and discipline my son can overcome these odds; but I must admit, my faith in this took a blow Saturday.

Scales of Justice, tlegend / Shutterstock.com

Oddly, I wasn't there the night George Zimmerman shot Trayvon Martin. I wasn't in the jury box either. Some commentators, like Ezra Klein and Ta-Nahesi Coates, are saying the not guilty verdict was appropriate according to Florida's "stand your ground" law. (Note that they are not saying that the Florida law is appropriate; Klein uses the word outrageous).

If this verdict was appropriate, though, what about verdicts in cases that were similar except for the color of the defendant? What happened to the "stand your ground" law when the jury reached its verdict against Marissa Alexander — an African American woman from Jacksonville, Fla.?

And anyway, why should fear of attack justify shooting to kill? It didn't in the case of John White — an African American man from Long Island, N.Y. — who shot a (white) teenager in 2006 (accidentally, he says, when the boy was trying to grab his gun).

John White, it appears, had good reason to fear the boys who showed up on his doorstep that night. That's probably why the governor commuted his sentence after he had served five months. And White no doubt should have served some time, according to New York law — his gun was unregistered, and if he hadn't been holding it when he went to the door, a scuffle probably wouldn't have escalated into manslaughter.

But, some say, the only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun. Is this true?

Grave marker showing face of sorrow, Hub.-Wilh. Domroese / Shutterstock.com

Carolyn Winfrey Gillette, a pastor who is a foster mother to a four year-old African American boy, wrote this hymn after George Zimmerman was found not guilty for his shooting of Trayvon Martin. She had read Jim Wallis’ “Lament from a White Father” and heard the Rev. Otis Moss of Chicago's Trinity United Church of Christ interviewed for the NPR report, “For The Boys Who See Themselves In Trayvon Martin.”

We Pray for Youth We Dearly Love

O WALY WALY LM (“Though I May Speak”)

Solo (optional young voice):

“If I should die before I wake,

I pray thee, Lord, my soul to take....

And if I die on violent streets,

I pray thee, Lord, my soul to keep."

(Continued at the jump)

President Obama tours the Martin Luther King, Jr., Memorial, RNS photo by Pete Souza/The White House.

I first learned about President Obama’s comments about racism and the Trayvon Martin case last week when a Facebook friend posted a link with this comment:

“Full text of the American President’s divisive and racist remarks today. He moves smoothly into his new role as race-baiter in chief.”

My friend’s anger was matched by many others from PowerLine to Breitbart. But what I read seems to me as controversial as tomorrow’s sunrise and incendiary as wet newspaper.

Let me try an analogy.

Imagine that Joe Lieberman had been elected our first Jewish president. And that in a moment of crisis, he felt compelled to explain that some reaction to even the hint of anti-Semitism is partly explained by the Jewish cultural memory of the Holocaust. And he included personal anecdotes about growing up Jewish in America.

Would he be accused of being divisive and guilty of whatever the Jewish equivalent of “race-baiting” might be?

Locked church doors. Photo courtesy vesilvio/shutterstock.com

Over the past week, as the nation has wrestled with the implications of the “not guilty” verdict in the George Zimmerman trial, I have concluded that many in white America are desperately trying to remind African Americans that, when it comes to race in America, silence is golden. Their effort implies that any honest dialogue about race that includes the stories and experiences of African Americans disturbs the idea of the “American experience” for those of a lighter hue.

This message came through loud and clear last Friday following President Obama’s unexpected and personal reflection on the death of Trayvon Martin and the verdict on the trial of George Zimmerman.

Crosses gathered for mourning. Photo courtesy Konstantin Yolshin/shutterstock.com

This morning I began preparing for a trip to Canada. I pulled out my grey North Park University hoodie to pack for the colder nights. Last year, a few days after the shooting of Trayvon Martin, North Park sponsored a justice conference. I wore that hoodie during my talk.

In retrospect, it feels like an empty gesture — an attempt to empathize with an experience that I, as a Korean-American, could never fully understand. In light of the Zimmerman verdict, I’ve been stunned into silence. I’m reeling from a deep disappointment in the American justice system and maybe even more distraught by the response of many in the white evangelical community that wants to argue the minutia of the law rather than trying to understand our brothers and sisters who are expressing a deep sense of lament.

The tragedy of Trayvon Martin requires an ongoing lament, which may be why it has been so difficult for evangelicals to engage on this issue.

President Obama addressed the nation today regarding the George Zimmerman trial, giving his thoughts on the nation's response to the verdict and the state of racism in our society.

Folks understand the challenges that exist for African-American boys, but they get frustrated, I think, if they feel that there’s no context for it or — and that context is being denied. And — and that all contributes, I think, to a sense that if a white male teen was involved in the same kind of scenario, that, from top to bottom, both the outcome and the aftermath might have been different.

You can read the full transcript of his speech here.

Hand and foot prints. Vector illustration courtesy ducu59us/shutterstock.com

What better way to honor Nelson Mandela on his 95th birthday today than to reflect on his concept of Ubuntu? Ubuntu, a word from the Bantu languages of southern Africa — roughly translated “I am because we are” — sums up Mandela’s approach to leadership, incorporating a generous spirit and concern for the wellbeing of one’s community.

Sign at a rally for Trayvon Martin. Photo courtesy Steven Ley/shutterstock.com

The acquittal of a person who is not black for the murder or beating of a black person is nothing new: Remember Yusef Hawkins. Remember Rodney King. Remember Amadu Diallo. Remember Alex Moore. Remember Latasha Harlins. Remember Sean Bell. Remember… remember… remember.

Many of us can recall these names without much effort. So, why is the death of Trayvon Martin so different?

It’s different because of the law — and the timing.

Cross detail in silhouette and the clouds in the sky. rui vale sousa / Shutterstock

Summertime is "revival season" for Christians of various denominations. Traditionally revivals, or "Great Awakenings", have preceded most major movements in American society, like the Revolutionary War and the Civil War. Revival involves not only a supernatural outpouring of the Holy Spirit but an intense time of confession, repentance, and crying out to God to make us and our communities right.

This summer will mark two major Civil Rights anniversaries: the 50th Anniversary of the March on Washington and 58th Anniversary of Emmitt Till’s death. It is my belief that providence provides us with divine appointments that can be overlooked as coincidences if we do not have the spiritual eyes to see. This summer appears to be one of those times of divine appointment.

The American Church has never truly mourned and repented of its original sin of racism, and sadly this sin has infected the Body of Yahshua (Christ) globally.

Young boy reaches to the sky. Photo courtesy Zurijeta/shutterstock.com

So,

No prom for you

Dear boy

No wedding

No children

No memories of you and family

For momma and daddy to savor

Just holes in their hearts to match

the hole

In yours

But as God is my witness

Sweet boy

You will never be forgotten

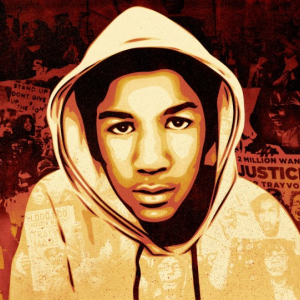

Trayvon Martin concept. Illustration courtesy benjaminisraelrobinson.com/wallpaperid.com

As we inched our way forward, the four lanes of the highway converged into one lane as we made our way around a terrible accident. We joined the long line of cars that passed the scene of the accident one by one, and we slowed — as did the others — to see what we could of the crash. But the moment we moved past the accident, the highway opened up to us, inviting us to freely and quickly accelerate.

And I began to think that tragedies like these cause us to slow down, and even come to a stop. They cause us to open our eyes for a moment and see that our actions have consequences. But on the other side of these tragedies, we tend to somehow find the freedom to move on, and to move on with strength. The only question is whether or not we will take what we see to heart, and resolve to be better drivers on the other side.

The metro is crowded today, and the 20-something, well-dressed white man has to stand, one hand holding the bar and the other his smartphone. It’s the end of the day. All the commuters — but one — are turned toward home. The young man’s face, like most of the others, is dulled with exhaustion. No one makes eye contact.

In a seat near the door, one woman sits facing everyone, looking backward. She studies the young man’s face intently, uncomfortably. He shifts. She rearranges the bags at her feet. Her reflection in the window shows an ashy neck above her oversized T-shirt collar. The train hums and clicks through a tunnel. As if in preparation, she takes another sip from the beat-up plastic cup she’s holding.

At last, she raises her voice and asks: “Why are white people so mean?” Boom! The electricity of America’s third rail crackles through the train. Faces fold in like origami or turn blank like a screensaver.

Distressed paper with American flag motif. Photo courtesy Andrey_Kuzmin/shutterstock.com

My father is white, and has lived a different story. My son was the same age as Trayvon Martin when Martin was killed in Florida in 2012. My white teenage son lives a different story. But when I got on a flight early on Sunday morning following the verdict, I was seated next to an African-American woman with six children. The weight of the verdict was on her face, and she showed me a photo of her three sons, all wearing hoodies, for whom Martin’s death and the subsequent verdict hit very close to home. This is their story.

Father and son embrace. Photo courtesy stefanolunardi/shutterstock.com

Howard Thurman says three things, in Jesus and the Disinherited: One — God is on the side of the oppressed and the poor. Know that God is on your side. Two — Dishonesty takes you out of the conversation. And if you live an honest life, if you have integrity, you can sit at the table. In areas of race, people look for holes in your character as excuses for you not to be at the table. Three — Hate is useless. Don’t let hate sink into your soul, because hate will destroy you. And respond with love even if it’s hard. So I try to teach my boys that, and raise them that way.

Hands held in a circle. Photo courtesy Brett Jorgensen/shutterstock.com

Death is horrible enough. But systematic injustice — one that allows white boys to assume success, yet leads black boys to cower from the very institutions created to protect our own wellbeing — is a travesty. Listen to the stories from Saturday and Sunday nights, of 12-year-old black boys who asked to sleep in bed with their parents because they were afraid. If black youth in America can’t rely on the police, the law, or their own neighborhood for protection — where can they go?

Hand painted acrylic United States of America flag. donatas1205 / Shutterstock

The recent “not guilty” verdict out of Sanford, FL, reflects the principle of the American legal system that if there is reasonable doubt, courts will err on the side of innocence. I dispute neither the principle nor the decision by the jury. But that doesn't leave me satisfied about the outcome.

Jesus said that true justice exceeds that of “the scribes and Pharisees” — and the same could be said of the prosecution and defense. Legal justice seeks only to assign guilt or innocence. Holistic justice works for the life, liberty, and well-being of all. And it especially works for reconciliation between the two Americas that can be identified by their reaction to the case.