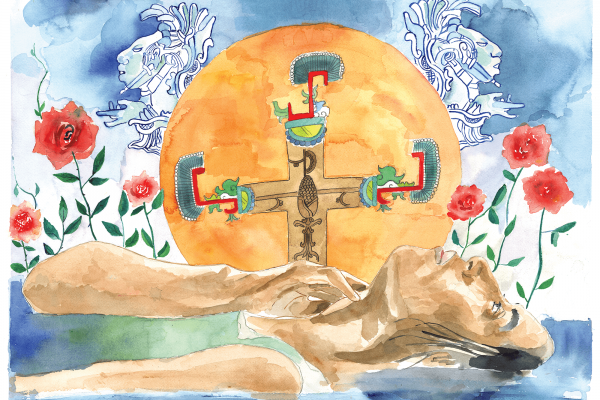

WHEN MAYA COMMUNITY educator Wilma Esquivel Pat opened a recent forum on the autonomy of Indigenous peoples, her remarks recalled her people’s struggle for self-determination in the Caste War of Yucatán—175 years ago.

European descendants had built lucrative sugar cane and henequen plantations on the peninsula that depended on Maya peasant farmers’ bonded labor. While the abolition movement was washing across the Americas, landholders on the Yucatán Peninsula began selling Maya prisoners of war and debtors into slavery in Cuba. In 1847, the Maya revolted and established an autonomous government in the eastern part of the peninsula that lasted through the turn of the century.

The era Esquivel Pat brought to mind remains recent, in generational time, for many Maya in attendance at the forum. Elders who held them as children may have themselves been cradled in the arms of elders who participated in that historic struggle. In them, their ancestors’ legacy reaches into the present. It’s a birthright they recall with pain and pride—the generations who resisted, as well as the white settlers and upper echelons of the colonial caste system who privatized land, exploited labor, and extracted returns at the expense of most of the region’s people.

Read the Full Article