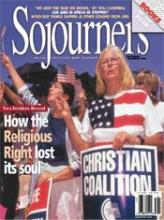

Everybody loves to quote the famous dictum by Lord Acton, "Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely." Heads nod all around, and then everyone ignores what the wise old Englishman said. Power does indeed corrupt human beings: It compromises principles, it quiets conscience, and it mellows morality. Power tells us to just get along, instead of getting upset; it encourages us toward smooth sailing, and discourages us from rocking the boat.

But it’s bad theology to say that power, per se, is always bad. The Bible speaks of the power of God, the power of the gospel, and the power of truth. The New Testament word dunamis means "spiritual power." Even political power (which is what Acton was really talking about) isn’t always evil. Look at the moral power and authority that Nelson Mandela exercised to free South Africa or the power of the civil rights movement which changed the landscape of American life. Yet power, and especially political power, is very dangerous. It’s often riddled with the hubris and illusion to which we all are so susceptible.

Human beings seem not to handle power very well. Of all people, religious leaders ought to know that best. Instead, religious leaders are often among the most easily corrupted by power, especially when they get close to political power. Doug Coe, the father of the prayer breakfast movement, once told me that the best way to get religious leaders together was to invite them to a meeting with a powerful political leader. He said most church leaders generally ignored Jesus’ suggestion to take the humbler places at a banquet and wait until they are invited to "come up higher." Instead they jostle for the best positions and places at the events where the powerful gather.

Read the Full Article